Introduction to Shared Kitchen Storage

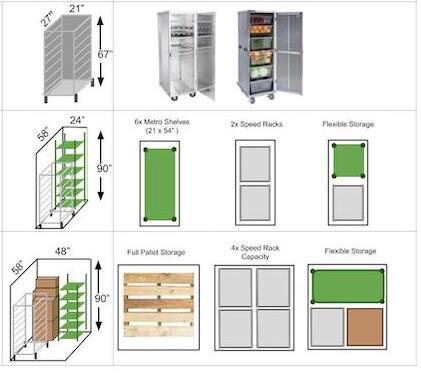

Your customers will probably want multiple options based on their business size

Storage can be a thorny area for shared kitchen operators. Food producers are typically interested in storing some combination of equipment, ingredients, and finished product onsite. Often, designated storage spaces are shared among multiple businesses. This requires the shared kitchen user to store their product in a set of containers.

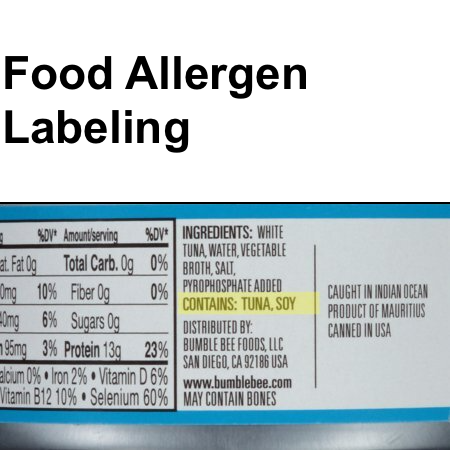

This section is devoted to helping you find the best storage containers for use in a shared kitchen. It is informed by the FDA regulations, collaboration with health agencies nationwide, and the best practices I’ve observed in shared kitchens.

Or, you can skip to the FDA Reader List of Best Shared Kitchen Storage Containers.

Factors to Consider

Here are the major considerations:

Material

Size

Airflow

Secure

Compatibility with other systems

Material

Food Safe: The material for your storage should be food safe — presumably there will be some contact between raw food (or packaging) and the container it will reside in. Ideally, the container is NSF approved, but if not, you should be able to discern whether it is made from food safe materials by reviewing the product spec.

Strong: You want a material that is going to be strong enough to endure the abuse of a kitchen. These containers will be full of heavy items, slammed down on tables, and dragged across wire shelves. It should be strong and also capable of enduring the temperatures of a refrigerator or freezer. While I recommend using metal bun-cabinets for easy storage, the cold can burn your hands when it has been sitting at -10ºF.

Color: Finally, it’s worth considering the color of the container. Since these containers might crack and they will be in close proximity to food, it’s best to get a color that will easily stand out (like blue). This is not necessary, but if color is a consideration, pick blue, the best color for minimizing foreign object contamination.

Water/Rust Proof: The storage container is going to get dirty and require washing. If it goes in the freezer, it will get covered in ice. Pick something that won’t rust and that can tolerate a lot of moisture. Wood and cardboard are no-no’s. Plastic and certain types of metal tend to work best.

Shape/Size

There are a few considerations when it comes to picking a storage solution. Ultimately, the most important considerations are what you are actually storing. You’ll want to make sure that your storage containers don’t affect the product stored inside them.

Weight An oversized plastic tote might fit all of your ingredients and equipment with ease… but it’s impossible to lift onto the shelf. If your container will live on a shelf, then pick a storage container that you can comfortably lift when it’s full.

Shape Avoid shapes that will minimize the amount of usable space, such as a box with walls that taper. Make sure the containers that you choose maximize the total space available on the shelf or in the space where they will live. Remember, finding the right storage container is being realistic about what is being stored.

Vented

If your storage container is going to live in a refrigerated or frozen environment, then it needs to be vented. Refrigeration works by blowing cold air across the surface of the food items in the space. If food is stored in a solid-walled container — e.g. a typical plastic storage box— the container will insulate the food and prevent it from cooling down.

This is a problem. Airflow is important for cooling purposes. This is why milk crates are crates not solid walled boxes.

The storage container should be vented to allow air to pass through it and across the surface of the food inside.

This is for you if...

∆ You are considering or purchasing storage solutions for use in a shared kitchen.